“Art is a circle, you’re inside or outside, by accident of birth.”

Manet

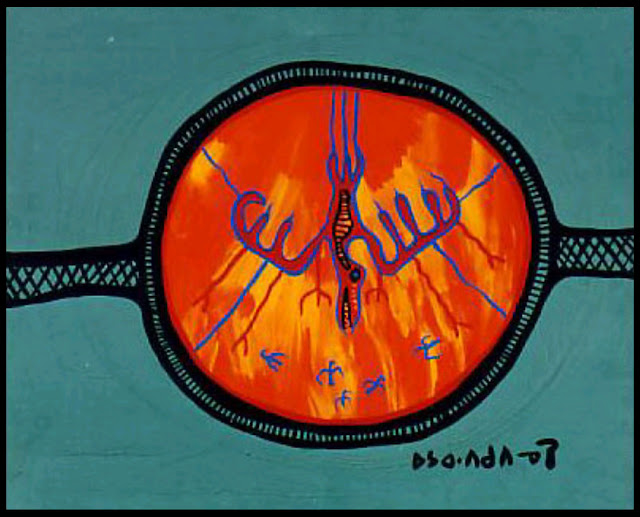

Thunderbird and Swallows

Norval Morrisseau

acrylic on canvass, 24" x 30“

IN MEMORIAM - NORVAL MORRISSEAU

Norval Morrisseau died yesterday at the Toronto General Hospital of complications from Parkinson's disease. Named after a powerful and fantastic celestial cultural hero in Anishnabe mythology, Norval was indeed Copper Thunderbird. Apart from the romantic and exotic resonance of this spiritual name, it also signified a cultural context with which his magnificent artistic output could be framed. I am honoured to have been asked to write a few words about this great artist, someone I considered neejee, a friend.

It is my humble desire to acquiesce to this shaman who lived among us for a while and became a cultural revolutionary of great stature. His colourful and enigmatic imagery will continue to inspire us all, it will articulate the visual landscape of the Ojibway people he loved so much, and his art will find a voice in the polemics of contemporary art in our country. His legacy, through his art with its mythological elements, will always mesh with a multitude of colours to a particular end: emancipation, narration, resistance, prophecy and pride.

Norval, whom I first met thirty years ago while doing a research paper commissioned by the Canadian Museum of Civilization, was both a mentor and a challenge. As a young Saulteaux from Manitoba, I originally found his subject matter familiar, but nonetheless, the illustration of mythology up to that moment had always been under the governance of shamanism. Needless to say, I was spellbound yet apprehensive of what Norval was sharing with the international viewing public and by the palette he used: charcoals and ochres, red and green oxides, black and white. I immediately referenced ceremonial and ritual art, something that had always been exclusive but made inclusive by Norval. -

We talked endlessly about understanding the truth about why we make art and his impromptu visits led to numerous discussions on world culture from an Anishnabe perspective. As speakers of the language, he, Ojibwa and me, Saulteaux, we met at a level where the esoteric issues of art making were never talked about, but rather we would focus on the practical problems of finding a market that would support our art or a future that would buttress our desire to tell the Anishnabe story. He was fun, helpful, and inspiring, qualities that contributed to a continuing relationship of respect and camaraderie, of being Anishnabec. -

Over the years, Norval popped in and out of my life, but was always close enough to know that he could drop by to continue talking about the knowledge acquired through his travels, whether physical or astral, in the afternoon or evening. His nonlinear storytelling allowed us all to travel along with him to uncharted worlds of history, music and art. I treasure those moments, for they remind me what a great person he truly was.

The iconoclastic Morrisseau tableau is a sensuous interplay of paint, colour and image; a diorama delineated by the beginning of a cultural conceit based on mythology and art. Copper Thunderbird spoke of a cyclorama where people, animals, birds, fish, plants and demi-gods negotiated an existence over lands, highways, rivers and lakes.

Norval, like all innovators, had made a trajectory to contemporary cultural theory, an idea I was not to understand until quite recently. It situated Norval at the centre of a cultural transformation, contemporary Ojibwa art. This legendary artist had created a visual language whose lineage included the ancient shaman artists of the Midiwewin scrolls, the Agawa Bay rock paintings and the Peterborough petroglyphs. As a master narrator, he had a voice that thundered like the sentinel of a people still listening to the stories told since creation. Indeed, for me, he invented an interior colour space where the imagination with its paradigms, viewpoints and methods was in complicity with the potent traditions of critique and resistance. He was a conjurer, orchestrating themes that offered a voyage into the spiritual, the fantastical and the outrageous.

A Morrisseau painting is an articulation, a manifestation that verifies existence and formulates an identity completely intermingled with the past and the present. Its virtual space, invented by colour and content, is actually an inner space where mythology and reality are interchangeable. Despite his detractors and in spite of himself, Norval stood tall and unequivocal within the context and usage of the current art lexicon. The art of Norval Morrisseau is a beacon of post-colonial resistance and is unequalled in its originality - the true sign of an artist. Kitchi Meegwetch Norval, we will miss you.

Robert Houle

December 5th, 2007